Exhibition at Jewish Museum of Belgium traces backgrounds of heroes including Superman, Batman and Captain America

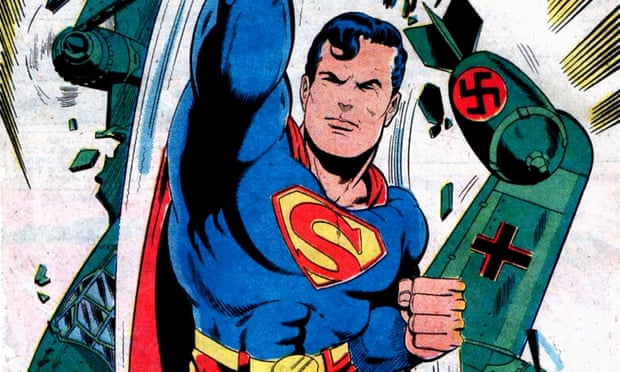

It was February 1940 when two American friends dreamt up how Superman would stop the second world war.

“Put me down! You are hurting me,” Adolf Hitler protests to the man of steel. But Superman has other ideas. Seizing the Nazi dictator, Superman shoots into the air, faster than any plane, to pick up Josef Stalin in Moscow. Next stop Geneva to drop off the “power mad scoundrels” at the League of Nations, where they are found guilty of “unprovoked aggression against defenseless countries”.

The cartoon strip How Superman Would End the War appeared in Look Magazine, almost two years before the US entered the conflict against Nazi Germany as allies of the Soviet Union. At the time, few knew that the creators of Superman, the scenarist Jerry Siegel and the draughtsman Joe Shuster, were children of Jewish immigrants.

An exhibition at the Jewish Museum of Belgium in Brussels is tracing the Jewish backgrounds of the US’s best-known superheroes, including Superman, Batman and Captain America.

The exhibition’s curator, Bruno Benvindo, believes firstand second-generation Jewish immigrants to the US were drawn to comics, partly because of low barriers to entry. “You don’t need a lot of technology to make a comic, just a pen and a good story,” he says.

He adds: “I am not saying it was easy for them. It was very hard because the publishing houses were ruthless for these young and sometimes naive creators.”

Siegel and Shuster sold the rights to Superman for $130 in 1938. They spent years on the breadline before Warner, the Superman filmmaker and then comic’s owner, agreed in the 1970s to give them a pension.

The exhibition traces a century of American comics, starting with the basic three-box strips in newspapers, often in “Yinglish”, a mix of Yiddish and English. One was Abie the Agent, a car salesman, created by Harry Hershfield, the son of a Jewish immigrant, Abie was the first Jewish character syndicated across the US.

In the late 1970s Will Eisner, a pioneer of the industry, wrote A Contract with God, a semi-fictionalised account of a Jewish family in the Bronx that transformed the comic into the graphic novel.

Eisner inspired Art Spiegelman, who won a Pulitzer prize for Maus, which recounts how his father survived Auschwitz.

Persecution was also explored in popular culture by the duo who created Captain America and Hulk, in their later series X-Men, launched in 1963. Jack Kirby and Stan Lee were both sons of Jewish immigrants. In X-Men, mutants are victimised for their differences.

Superheroes Never Die, at the Jewish Museum of Belgium, until 26 April

“Put me down! You are hurting me,” Adolf Hitler protests to the man of steel. But Superman has other ideas. Seizing the Nazi dictator, Superman shoots into the air, faster than any plane, to pick up Josef Stalin in Moscow. Next stop Geneva to drop off the “power mad scoundrels” at the League of Nations, where they are found guilty of “unprovoked aggression against defenseless countries”.

The cartoon strip How Superman Would End the War appeared in Look Magazine, almost two years before the US entered the conflict against Nazi Germany as allies of the Soviet Union. At the time, few knew that the creators of Superman, the scenarist Jerry Siegel and the draughtsman Joe Shuster, were children of Jewish immigrants.

An exhibition at the Jewish Museum of Belgium in Brussels is tracing the Jewish backgrounds of the US’s best-known superheroes, including Superman, Batman and Captain America.

The exhibition’s curator, Bruno Benvindo, believes firstand second-generation Jewish immigrants to the US were drawn to comics, partly because of low barriers to entry. “You don’t need a lot of technology to make a comic, just a pen and a good story,” he says.

He adds: “I am not saying it was easy for them. It was very hard because the publishing houses were ruthless for these young and sometimes naive creators.”

Siegel and Shuster sold the rights to Superman for $130 in 1938. They spent years on the breadline before Warner, the Superman filmmaker and then comic’s owner, agreed in the 1970s to give them a pension.

The exhibition traces a century of American comics, starting with the basic three-box strips in newspapers, often in “Yinglish”, a mix of Yiddish and English. One was Abie the Agent, a car salesman, created by Harry Hershfield, the son of a Jewish immigrant, Abie was the first Jewish character syndicated across the US.

In the late 1970s Will Eisner, a pioneer of the industry, wrote A Contract with God, a semi-fictionalised account of a Jewish family in the Bronx that transformed the comic into the graphic novel.

Eisner inspired Art Spiegelman, who won a Pulitzer prize for Maus, which recounts how his father survived Auschwitz.

Persecution was also explored in popular culture by the duo who created Captain America and Hulk, in their later series X-Men, launched in 1963. Jack Kirby and Stan Lee were both sons of Jewish immigrants. In X-Men, mutants are victimised for their differences.

Superheroes Never Die, at the Jewish Museum of Belgium, until 26 April

Comments

Post a Comment