| 1900 | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster

| |

| Directed by | Bernardo Bertolucci |

| Produced by | Alberto Grimaldi |

| Screenplay by | Franco Arcalli Giuseppe Bertolucci Bernardo Bertolucci |

| Starring | Robert De Niro Gérard Depardieu Dominique Sanda Francesca Bertini Laura Betti Werner Bruhns Stefania Casini Sterling Hayden Anna Henkel Ellen Schwiers Alida Valli Romolo Valli Stefania Sandrelli Donald Sutherland Burt Lancaster |

| Music by | Ennio Morricone |

| Cinematography | Vittorio Storaro |

| Edited by | Franco Arcalli |

Production

company | |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox (Italy and UK) Paramount Pictures (US) United Artists (International) |

Release date

| |

Running time

| 317 minutes 162 minutes (Part 1) 154 minutes (Part 2) 247 minutes[1] (Edited version) |

| Country | Italy France West Germany |

| Language | Italian French German English |

| Budget | $9 million[2] |

With a runtime of 317 minutes in its original version, 1900 is known for being one of the longest commercially released films ever made. Due to its length, the film was presented in two parts when originally released in many countries, including Italy, East and West Germany, Denmark, Belgium, Norway, Sweden, Colombia, Pakistan and Japan. In other countries, such as the United States, a singular, edited-down version of the film was released.[4] 1900 has become widely regarded as a cult classic, and the film received special edition home video releases from Paramount, Fox and other distributors worldwide.[5][6] The film's restored version premiered out of competition at the 74th Venice International Film Festival in 2017.[7]

Contents

Plot[edit]

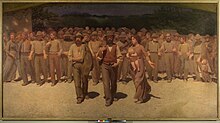

The initial credits are displayed over a zoom out of Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo's The Fourth Estate.

The narrative moves back to the start of the century. Born on the day of the death of composer Giuseppe Verdi – 27 January 1901 – Alfredo Berlinghieri and Olmo Dalcò come from opposite ends of the social spectrum. Alfredo is from a family of landowners led by his popular grandfather (also called Alfredo) and grows up with his cousin Regina. Olmo is an illegitimate peasant. His grandfather, Leo, is the foreman and peasants' spokesman who carries out a duel of wits with the elder Alfredo which masks a deep-seated mutual respect. As Alfredo is somewhat rebellious and despises the falseness of his family, in particular his weak but abusive and cynical father Giovanni, he befriends Olmo, who has been raised as a socialist. During this time, Leo leads strikes against the unfair conditions on the farm.

The two are friends throughout their childhood, despite the social differences of their families, and spend much time in one another's company. Olmo enlists with the Italian army in 1917 during World War I and goes off to fight while Alfredo learns how to run his family's large plantation under the guidance of his father. Olmo returns from the war over a year later and his friendship with Alfredo continues. However, Giovanni, the padrone since the elder Alfredo's suicide, has hired Attila Mellanchini as his foreman. Taken with fascism in a similar way that Giovanni has been, Attila eventually incorporates his new belief system in his dealings with the Berlinghieri workers; he treats them cruelly, and wins Regina and Giovanni over to his side. By the 1920s, Olmo has entered into a relationship with Anita, a down-to-earth woman who shares his enthusiasm for the cause of workers' rights. Together, Olmo and Anita lead several fervent protests against the landowners.

Following the death of Giovanni, Alfredo becomes the new padrone and marries Ada, a gorgeous, demure Frenchwoman. During the 1930s, he proves to be a weak padrone, repeatedly bending to the whim of the fascists. Ada sinks into alcoholism when confronted with the reality of the emptiness of her marriage to Alfredo; she sympathises to some extent with the workers and despises Alfredo for his failure to stand up to Attila. As Olmo takes on his fateful role of leader among the poor farmers and their families, he clashes with Attila. The latter, whose violent tendencies have been revealed via the murders of a cat and a small boy (the latter at Alfredo and Ada's wedding and for which Olmo was initially blamed), commits further atrocities such as killing the elderly Mrs. Pioppi in order to steal her land and home. However, he becomes a fresh target of ridicule at the hands of the peasants; led by Olmo, they take turns throwing manure at him, and Alfredo fires him (although this does not win Ada's respect as he has hoped it would, and she leaves him). Olmo flees to keep from being killed by the fascists, and Attila reacts to the humiliation by tearing up Olmo's house with his blackshirts before caging the peasants on the Berlinghieri compound and indiscriminately shooting them.

The story comes full circle when the power shifts after World War II in 1945, and the ruling class is at the mercy of the jovial yet bitter farm labourers. Attila and Regina, having been apprehended, are imprisoned in the Berlinghieri pigsty, and the women peasants cut off Regina's hair. Attila confesses to the murders he has committed over the years, and is put to death. Olmo returns to the farm in time to see Alfredo being brought before a workers' tribunal to stand trial. Many workers come forth and accuse Alfredo of letting them suffer in squalor while he profited from their labours. Alfredo is sentenced to death, but his execution is prevented after Olmo explains that the padrone is dead, so Alfredo Berlinghieri is alive, suggesting that the social system has been overthrown with the end of the war. As soon as the verdict is reached, however, representatives and soldiers of the new government, which includes the Communist Party, arrive and call on the peasants to turn in their arms. Olmo convinces the peasants to do so, overcoming their scepticism. Alone with Olmo, Alfredo declares "The padrone is alive", indicating the struggle between the working and ruling classes is destined to continue.

Comments

Post a Comment