Article by D.K. Johnson in Psycology Today; "The Handmaid’s Tale, Feminism, and the Dangers of Religion"

The Handmaid’s Tale, Feminism, and the Dangers of Religion

Is The Handmaid's Tale pro-feminst? Is it anti-religous?

The Hulu series The Handmaid’s Tale launches its second season tomorrow. Although it is based on Margaret Atwood’s novel of the same name, the first season ended where the book did—so the second season will almost necessarily go beyond it. Where they go with it will be interesting, especially given that Atwood herself is involved heavily in the project. Apparently, it’s going to be even darker.

Regardless of where they go, however, the two questions Atwood says she is most often asked about her work will likely remain: “Is it feminist?” and “Is it anti-religious?” I tackle these questions directly in my course Great Courses course, Sci-Phi: Science Fiction as Philosophy (available June 2018). But in anticipation of the number of people that will be watching the two episode season 2 opener tomorrow, I’d like to spend a little time addressing these two questions here. But first, a little set up.

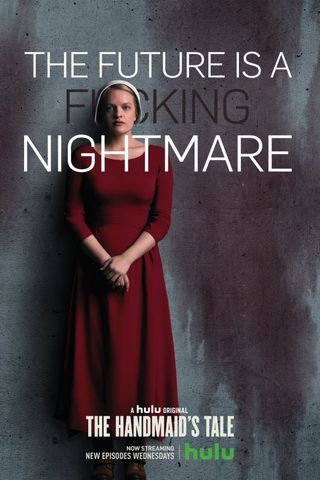

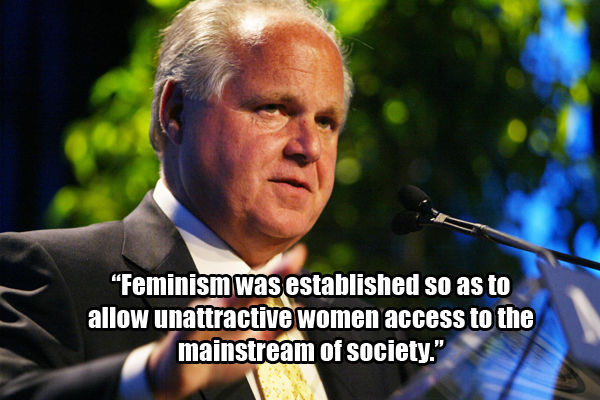

Teaser Poster from Season 1

Source: Hulu/Coming Soon

The attention The Handmaid’s Tale has received is largely due to people’s worries that something like what happens in the novel could actually happen to us. As Atwood herself said about her motivation for writing the novel: growing up during WWII taught her "It can’t happen here" [can’t] be depended on. Anything [can] happen anywhere, given the [right] circumstances. Indeed, The Handmaid’s Tale does not involve, as Atwood put it, “any technology not already available. No imaginary gizmos, no imaginary laws [and] no imaginary atrocities.” Atwood did not (quote) “put any events into the book that had not already happened in what James Joyce called the ‘nightmare’ of history.” Governments have been toppled and women have been treated in exactly the ways it describes.

The Handmaid’s Tale takes place at an unspecified future time, when infertility is sweeping across the world and Puritan fundamentalism has resurfaced. These new Puritans see the infertility as God’s judgment on a secular society—a society in which women [quote] “dressed like sluts,” engaged in sex purely for pleasure, and avoided the consequences with birth control and abortion.

To take control of the government, the puritans assassinated the President and Congress and then blamed Islamic fundamentalists. This enabled them to suspend the Constitution, establish martial law, and eventually institute a Christian theocratic government known as the Republic of Gilead—in which women are denied the right to own property, have money, maintain a job—or even read.

All women not with their first husband are considered adulterous wards of the state. The few who are fertile are re-educated in boot-camp-like “red centers”—where they’re cruelly indoctrinated into their “duty” to God and country to “ensure the survival of humanity” by bearing children for the elite of the theocratic government. Upon graduation, these “handmaids’ are forced to wear red habits and white bonnets, to indicate their status.

The Handmaid’s Tale is the story of one such woman whose name (as revealed in the Hulu series) is June. As the second wife of a man named Luke with whom she had a child, June is the perfect example of what Gilead is looking for. Captured upon trying to flee to Canada, her child and husband are taken from her and she’s sent to a red school—and then to serve as handmaid for a commander in the republic named Fred. Because she now “belongs” to him, she’s known simply as “Offred” … “of Fred.”

Her main duty is to conceive a child…which she must attempt to do in a horrific ceremony where she lays between the legs of Fred’s wife, Serena Joy, while the commander tries to impregnate her. To justify the ceremony, commanders quote scripture before it begins—Genesis 30, where Jacob’s barren wife Rachel offers up her handmaid Bilhah (Bee-Law) so that Rachel “may also have children by her.” The act is for procreation only—Offred’s red habit is merely lifted and she still wears the bonnet.

Since The Handmaid’s Tale depicts the plight of women in an abusive patriarchal society ruled by religious fundamentalists, the two most common questions Atwood says she is asked about The Handmaid’s Tale are these: (1) Is it feminist? And (2) Is it anti-religious?

To these questions, Atwood essentially answers in the negative. She does not seem to see it as either a feminist story or an anti-religious story. But to those familiar with the work, this seems odd; it seems to be, blatantly and obviously, both. So it is to answering the questions of whether or not The Handmaid’s Tale really is feminist or anti-religious that this paper shall be devoted.

The Death of the Author

Source: wikimedia

We must first begin, however, by wondering why any time needs to be spent answering these questions at all. “If Atwood says it’s not feminist or anti-religious,” one might argue, “then it’s not. She’s the author. She gets to determine that.” But this argument endorses a philosophic view called intentionalism that many philosophers and artists reject.

Intentionalism is the view, defended by philosophers like Paisley Livingston, that the meaning of a work of art is determined wholly and solely by the intentions of its author. Whatever they say the meaning of the work of art is, is its meaning. But many philosophers, like Roland Barthes, author of The Death of the Author, reject this idea. As Ruth Tallman puts it, there are essentially three problems with intentionalism.

First, it leaves many works of art with unknowable meaning or even no meaning at all. Many works of art have unknown authors, and thus (on intentionalism) knowing their meaning would be impossible. What’s more, some authors have expressly said that their work has no meaning—but that doesn’t make it so. For example, about The Lord of the Rings J. R. R. Tolkien said: “As for ‘message,’ I have none really, if by that is meant the conscious purpose in writing The Lord of the Rings, of preaching, or of delivering myself of a vision of truth specially revealed to me! I was primarily writing an exciting story in an atmosphere and background such as I find personally attractive.” In other words: “Here's a story, I hope you enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed writing it.” But that doesn’t mean that Lord of the Rings has no meaning. It contains clear morals about friendship and the conflict between good and evil, and also contains commentary on the European politics of its time.

The second problem with intentionalism is that makes the meaning of art static—locked into place by the author’s intentions. But art can take on new meaning as society changes around it. Take The Twilight Zone episode “A World of His Own,” for example. In it, a man is able to create his ideal woman by merely describing her into a tape recorder. In the 60s, this likely conveyed a message about being happy in one’s marriage. Today, it would likely serve as a commentary on misogyny. And if people one day are falling in love and having sex with robots—as author David Levy predicts in Love and Sex with Robots—it will take on an entirely new meaning.

A piece of art can also take on a new meaning as other art is developed around it. Consider how Rogue One: A Star Wars Story changed how so many view the original 1977 Star Wars. By explaining the Death Star’s “design flaw” as a deliberate act of sabotage, many think it actually made the original movie better.

Third, intentionalism also seems to neglect the importance of audience interaction. Philosopher Arthur Danto argues that argues that, by its very nature, art is public—and as such, it invites the audience to interpret it…to “finish” it even. Once completed, a work of art is the property of society, not the author. Correspondingly, everyone is invited to interpret it and discover it’s meaning.

Now, none of this means that you can just interpret a piece of art however you want. Logically, for example, a good interpretation of a film can’t contradict basic facts of the film. You might suppose something happened off screen, but you can’t ignore what does happen on screen to bolster your favored view.

What’s more, the principle of charity demands that you not embrace an interpretation that makes the work or author seem worse than they otherwise would be. Unless we have sufficient evidence to the contrary, we should assume the author isn’t an idiot.

Context also matters…and so do authorial intentions. They’re not the final arbiter, but they can help. Steven Spielberg’s intentions, for example, in making Schindler’s List make it clear that it could never be legitimately interpreted as a “pro-Nazi” film.

In my course, Sci-Phi: Science Fiction as Philosophy, I always use the most philosophically interesting interpretation, and indeed, try to interpret to work as something that is putting forth a philosophical argument—which, interestingly, is often the author’s intention.

With that in mind, we must now turn to asking whether The Handmaid’s Tale is putting form an argument in favor of feminism. In other words….

Source: pinterest

Regarding this question, Atwood is very careful in her answer:

"If you mean an ideological tract in which all women are angels and/or so victimized they are incapable of moral choice, no. If you mean a novel in which women are human beings—with all the variety of character and behavior that implies—and are also interesting and important, and what happens to them is crucial to the theme, structure and plot of the book, then yes. In that sense, many books are 'feminist'.”

Indeed, by that definition, any story with a sympathetic female protagonist is feminist. This is why it seems Atwood thinks The Handmaid’s Tale isn’t feminist. It’s no more feminist than many other stories, many of which wouldn't be considered feminist, so it’s not really feminist at all.

In that it aims to carefully clarify definitions, Attwood’s answer is very philosophical—but it doesn’t actually help us answer our question…and not just because we are not letting authorial intentions define meaning. Another problem is this: The definitions of feminism Atwood offers don’t match up to how people usually conceive of feminism; so whether or not The Handmaid’s Tale matches up to these definitions doesn’t tell us whether it’s a feminist tale.

Generally, feminism is thought to be the idea women are of equal value to, and deserve all the same rights as, men; sexism should end and women deserve justice for the ways they have been wronged. But even what that exactly means—what counts as sexism, what ways have women been wronged, what does it mean to be of equal value, what form should justice take—is debatable. So the best way to answer our question is to look at the ways that feminism have been defined over the years—and what ideals and goals is has sought—and then ask whether The Handmaid’s Tale endorses those ideals and goals. And to do this, it seems that we should consider The Handmaid’s Tale in light of the acknowledged the three waves of feminism. So let’s examine each in turn.

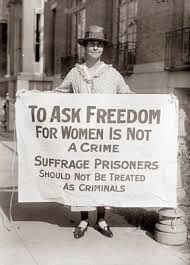

Source: Pinterest

First wave feminism’s breakout moment was the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848—a women’s rights convention in New York involving 300 men and women. Written primarily by Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815–1905), the convention’s Declaration of Sentiments argued that women and men were naturally equal, and proposed a political strategy by which women could attain equal access and opportunity in the political system. This, of course, mainly involved women gaining the right to vote and first wave feminism is most closely associated with women’s suffrage. Indeed, the first wave is generally thought to have ended when the 19th Amendment passed.

But this was not the only goal of first wave feminists. Many were founders of the temperance movement, aimed at making alcohol illegal in an effort to guard against the domestic abuse (and many other problems) suffered by women at the hands of alcoholic husbands and boyfriends.

This went hand-in-hand with their fight for women’s ability to be more independent of their husbands, including a desire for equal opportunity (and pay) in the workforce, equal access to education, and equal protection under the law when it comes to divorce. Indeed, one of the sentiments that came out of the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention observed how heavily the laws of divorce favored men, making it easier for men to leave their wives unjustly, and harder for women leave abusive or negligent men. And, indeed, first wavers did win the legal “right to divorce, to own property, claim inheritance and to keep their own names”—although the laws that were passed still greatly favored men.

First wavers also fought for the abolition of slavery—after all, both women and slaves were fighting against white male dominance—and some famous first wave feminists were woman of color—like Maria Stewart, Frances Harper, and Sojourner Truth.

Early on, the movement also included working-class women; but by the end, first wave feminism mainly involved, well-educated, middle-class white women. In fact, it may have been a group of such women being arrested for protesting in front of the White House in 1918 (and other events like it) that finally led to public sympathy for the movement and served as the catalyst for the passage of the 19th Amendment two years later. They may have been running against traditional gender roles by being outside the home and engaging in public dialogue, but these were well-educated white ladies dressed in their Sunday best. Arresting working class and black women was one thing, but for the American public, arresting “lady-like ladies” was a step too far. (Compare this to how black youth have been advocating for gun laws for years, but it took white kids in Florida to step up for the public to pay attention.)

First Wavers protesting in front of the White House in 1918.

Source: Global Citizen

When considered in this light, The Handmaid’s Tale clearly endorses feminist ideals. Although first wavers might have liked the fact that Gilead bans alcohol, all the others rights the first wave feminists fought for were stripped away in Gilead; not only is slavery in many forms common, but women in particular have been stripped of the right to vote, the right to own property, have a job, to have money….even the right to read. The place of the women is once again only in the home, and reproduction and the care of husbands and children is their only role. Men dominate and control society and women, not like they did in the 1800s, but like they did in the 1600s. Indeed, Atwood says that Gilead reflects a revival of the Puritan religious beliefs of those who colonized America. It’s no coincidence that the story is set is Massachusetts. One moral of the story must be to not take the accomplishments of first wave feminism for granted.

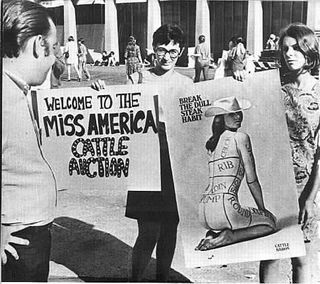

Second Wavers Protesting the Miss America Pageant in 1968

Source: Protesting Miss America 1968/ The Veteran Feminists of America

Although the 19th amendment passed in 1920, by the 1960s it became clear that voting rights weren’t enough to secure the equalities the first wave wanted. Women still made up a small minority of the workforce, and the mere 38 percent of women that did work were primarily limited to being teachers, nurses, or secretaries—and actively prevented from professional programs, like medical and law schools. Women were expected to marry early, have children, and devote their lives to their families—spending 55 hours a week on domestic chores. They had little right to their husband’s earnings (while he could completely control theirs), and were subject to “head and master” laws that stripped women of all decision making power when it came to jointly owned property. Divorces were still easy for men to attain, while women were forced to prove wrongdoing in a court of law. Working women were paid smaller salaries, denied promotions, and often never hired at all (because employers assumed they would quickly become pregnant and quit anyway). And, of course, sexual expectations were asymmetrical—as they still largely are today. Promiscuous men were considered virile studs, promiscuous women dirty sluts.

Second wave feminism began in 1963, when Betty Friedan published The Feminine Mystique—and called attention to the plight of college-educated homemakers who were unsatisfied in their dull domestic life of serving food, cleaning clothes, and making beds. Not only were they bored; they felt they had no identity. Friedan called for them to find fulfillment in the workforce … and an entire generation responded.

But the movement quickly expanded. The “women’s liberation movement” fought for equal reproductive, sexual, property, and divorce rights. Soon to follow were Roe v. Wade, legal changes to property and divorce laws, altered sexual expectations, and oral contraceptives (which allowed women to pursue education and employment without worrying about pregnancy or allowing others to decide the purpose of their sexual activities).

The question of whether The Handmaid’s Tale endorses second wave feminism does not have a straightforward answer.

In some respects, it clearly does. For example, second wave feminists became famous for their protests of the Miss America pageant in the late 60s (pictured above). They likened the pageant to a cattle parade, where women are treated like slabs of meat—sexual objects instead of human beings. In Gilead, women are treated essentially the same way … especially the handmaids: as breeding stock. Their worth is determined by their fertility rather than their humanity. The aunts who run the red centers even tag the ears of handmaids and use cattle prods to keep them in line. “We are for breeding purposes,” Offred says in the novel. “We are two-legged wombs, that’s all.”

Aunt Lydia, right before she uses a cattle prod on June to "keep in her line."

Source: Glide Magazine/Hulu

Take Offred’s mother. She clearly is a second waver; she appears in old footage of protests for abortion rights, and complains that her daughter is not thankful for what the second wave accomplished. “You don't know what we had to go through, just to get you where you are,” she says, standing in Offred’s kitchen. “Look at [Luke] slicing up the carrots. Don't you know how many women's lives, how many women's bodies, the tanks had to roll over just to get that far?” And yet, her second wave feminism is vilified. Offred’s mother even complains about it herself—about how some of her fellow second-wavers tried to shame her for having a child.

Ironically, she in turn tries to force her version of feminism on Offred. “She expected me to vindicate her life …” Offred says. “[But] I didn't want to live my life on her terms. I didn't want to be the model offspring, the incarnation of her ideas.” In one troubling event when Offred was young, her mother lied to her, saying they were going to the park to feed the ducks, when she was really meeting up with her feminist friends to burn pornographic magazines.

This last detail is significant because some second wavers advocated for legal restrictions on pornography because of how it objectifies women—like Page Mellish who founded Feminists Fighting Pornography. As Gloria Steinem put it, “A woman reading a Playboy feels a little like a Jew reading a Nazi manual.” Indeed, some second wavers called for women to discard anything that might encourage their objectification. Susan Brownmiller argued against the use of makeup, keeping up with fashion, and even women’s magazines. Since all these things—pornography, fashionable clothes, women’s magazines, makeup … even hand lotion—are illegal in Gilead (they even burned pornographic magazines), one might be tempted to see the evil Gilead as a second waver’s paradise.

Ann Dowd as Aunt Lydia

Source: The Mike O'Meara Show/Hulu

But the temptation to think of Gilead as a second-waver’s paradise is ill-founded. Not only does Gilead stand contrary to the central tenants of gender equality championed by second wave feminism, but the anti-porn, anti-sex, anti-man movement represented only the left-wing-fringe of the second wave movement. So it would be a mistake to identify the entire movement with the, as Atwood puts it, “phase of feminism when you weren’t supposed to wear frocks and lipstick.”

Indeed, this seems to be why Atwood avoids the term feminism to describe her work. As she admitted to Rebecca Mead in the New Yorker, it was women calling themselves feminists who labeled Atwood a traitor to her sex for wearing lipstick and dresses. Since she doesn’t agree with that, or think of The Handmaid’s Tale as endorsing that view, she doesn’t see it as feminist. But, again, that’s not what feminism is. Most second wave feminists wore dresses and lipstick and didn’t hate men at all; indeed, they fought alongside men for women’s equality and sexual liberty.

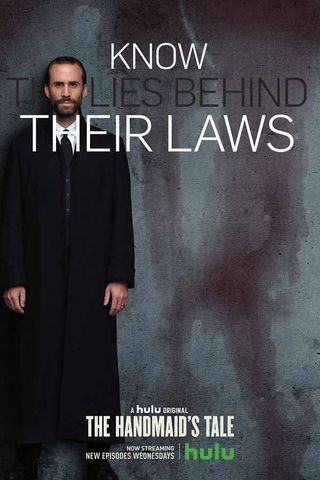

To be clear, although some second wavers, such as Kate Millett, did call for feminists to reject men and “choose lesbianism,” the picture of all feminists as militant lesbians who hate men is largely a product of the imagination of the right—like Rush Limbaugh, who popularized the term “feminazi.”

The Rush Limbaugh Show, April 10, 2009 (Hour 3)

Source: Public Health Watch/Wordpress

Offred herself certainly falls into this category. After Serena Joy arranges for the family’s driver, Nick, to try to impregnate Offred (because the Commander is likely sterile), Offred continues to return to Nick’s room for sexual encounters.

But speaking of the aunts…although the aunts (who are undoubtedly the story’s villains) may look and behave somewhat like the left-wing of feminism that vilified sexuality, it seems that another point of the story is to demonstrate how patriarchy can strip women of power so severely that it causes them to turn on each other. Indeed, that’s probably what made second wave feminists fight among themselves. So we can’t even view The Handmaid’s Tale as a condemnation of extreme left-wing second wave feminism. It’s primarily a condemnation of the patriarchy that lines up nicely with the tenants of second-wave feminism.

Historically, second-wave feminism might have also ended with the passage of an amendment to the constitution—in this case, the Equal Rights Amendment, which would have guaranteed legal equality for the sexes regarding employment, property, and divorce. But, although it passed both houses in the late 1970s, a conservative backlash after the election of Ronald Reagan (led by Phyllis Schlafly) kept the ERA from receiving the necessary ratifications from the states. So exactly when the second wave ended is a matter of debate.

Third Wave Feminism Emphasizes Diversity

Source: pintrest

Now, to what extent The Handmaid’s Tale aligns with third wave feminism is difficult to pin down because third wave feminism itself is difficult to pin down. Arguably, it came into existence with Naomi Wolf’s The Beauty Myth in 1990, or in 1992 when (in response to calls for a post-feminism era in the New York Times after the Anita Hill hearings), Rebecca Walker wrote in Ms. Magazine “I am not a post-feminism feminist. I am the Third Wave.”

There is no set leader of third wave feminism, however, and no one set doctrine or goal … perhaps because, given the era, its ideas largely spread online. As Dr. Charlotte Kroløkke puts it, “third-wave feminisms are defined not by common theoretical and political standpoint(s), but rather by the use of performance, mimicry, and subversion as rhetorical strategies.” Indeed, some of the major players in third wave feminisms include riot grrrl bands like Bikini Kill and activists/performance artists like Pussy Riot and Guerrilla Girls.

One thing most third wavers have in common, though, is that, while they acknowledge the third wave was made possible by rights the second wave secured, they’re also critical of the second wave in many ways—like how it was mainly something advocated for-and-by white middle-class women. Correspondingly, third wavers are much more aware and sensitive to the needs of minority women … and gender issues in general, conversing with and advocating for the rights of gays and transsexuals.

And, unlike some previously discussed second wavers, third wavers do not have restrictions for how feminists must present themselves. Third wavers generally advocate for anyone’s freedom to dress and act as they like, including dressing sexy and being sexual. Indeed, a woman’s sexuality can be used as a means to feminine power.

We see this in Atwood’s novel when Offred teases two Gilead guards who, she says, “aren't yet permitted to touch women.” She sways her hips, hoping to turn them on. “It's like thumbing your nose from behind a fence or teasing a dog with a bone held out of reach,” she says. “I enjoy the power; power of a dog bone, passive but there.”

Other third wave tropes abound in the Hulu episodes. The cast is notably more ethnically diverse than the novel’s—for example, June’s best friend Moria and husband Luke are both black—almost as if to make the point that feminism must address everyone’s problems, not just middle-class white women. And it also addresses the plight of gay people. Offred’s best friend, Moira, is a “gender traitor” … that is, a lesbian. And when Offred’s shopping partner, Ofglen, is identified as a “gender traitor” too, the regime attests her, performs a female circumcision on her (so she will “no longer want what she can’t have,”) and then hangs her lover right in front of her.

Source: screenshot/hulu

The Hulu series appropriates this appropriation itself. The Commander’s previous handmaid carved a phrase inside her closet: “Nolite te Bastardes Carborundorum”. It’s a pseudo-Latin phrase—in the book made up by the commander and his grade-school chums—that supposedly means “Don’t let the bastards grind you down.” The fourth episode ends with Offred leading a group of handmaids down the street, under dramatic music and the narration “There was an Offred before me. She helped me find a way out. She’s dead. She’s alive. She is me. We are handmaids. Nolite te Bastardes Carborundorum, bitches.”

In fact, the cast members of the Hulu series, in refusing to say that The Handmaid’s Tale is a “feminist story” at the Tribeca Film Festival, seem to have actually endorsed a third-wave feminist idea. While Elisabeth Moss (who plays Offred) says the show has no political agenda, Ann Dowd (who plays Aunt Lydia) wants it to inspire people to picket the White House in handmaid outfits—which they’ve done by the way. It’s just a story about human struggles, Moss said, because “women’s rights are human rights.” Yet that phrase was a feminist mantra even before Hillary Clinton uttered it in 1995 to the United Nations Fourth World Congress on Women. It’s almost as if they don’t want to tell people what it means for something to be a feminist show, just like third wavers want to avoid telling people what it means to be a feminist. So their refusal to call it a feminist show may, ironically, be what makes it a feminist show.

In that vein, I would never say that Atwood should just admit that her novel is a feminist story; she can view it how she wants. But in return, I would suggest that she not discourage others from finding a feminist message in it. (Fortunately, to my knowledge, she has not done so.)

Top Left to Lower Right: Dawkins, Hitchens, Harris, Dennett

Source: Wikipedia

But let us now turn to the second question Atwood is asked: Is The Handmaid’sTale anti-religious?

The term “anti-religious” is usually reserved for authors who argue against religion—such as the so-called New Atheists, like Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens, Sam Harris and philosopher Daniel Dennett—whose goal is to get people to stop being religious. To accomplish this goal—apart from trying to convince people that religion has natural (rather than supernatural) origins, and that religious doctrines (like “God exists”) are false—New Atheists try to convince you that religion is dangerous—that society would be better off without it.

This latter approach is embraced most directly by Harris and Hitchens in The End of Faith and God Is Not Great, where they detail the many atrocities committed in religion’s name. And the reason The Handmaid’s Tale seems anti-religious is because the atrocities the New Atheists mention mirror precisely those we see carried out in Gilead—everything from modern-day terrorism and the horrors of theocratic regimes who sacrifice heretics and “gender traitors,” to the general brutalization and mistreatment of women, both in and outside of marriage: female genital mutilation, honor killings, child molestation, restrictions of basic rights and education.

Atwood insists, however, The Handmaid’s Tale isn’t “anti-religious.” In her afterword, she points out that the resurgent Puritanism that dominates Gilead is also hunting down other Christians—Catholics, Baptists, Quakers. And some of these religions are active in the resistance—sneaking women into Canada, for example. And Offred herself is religious, saying her own version of the Lord’s Prayer in chapter 30. What The Handmaid’s Tale is “against,” Atwood says, is “the use of religion has a front for tyranny.”

We can see this in the show, as Aunt Lydia constantly quotes the Bible … but only the parts that are useful. “Blessed are the meek,” she says to Janine, leaving out the “inherit the earth” part ... before she has Janine’s eye plucked out for insubordination.

In the book, the Bible is added to freely because women are not allowed to read it. “Blessed are the silent,” a tape-recorded man adds to the beatitudes while the girls dine. And “from each according to her ability; to each according to his needs.” The girls are told this is from St. Paul in the book of Acts—but that’s actually a bastardized version of a phrase popularized by the communist Karl Marx, bent along gender lines to make it a command for women to serve men. Atwood’s point seems to be that the elite of Gilead are not truly motivated by scripture. They use it, and people’s loyalty to it, to secure power.

Source: poster/hulu

And so, the argument goes, religion’s not dangerous—it’s just its misuse that’s dangerous. Indeed, those who misuse it aren’t really religious. They don’t really believe the doctrines they espouse; they don’t really cherish the holy books they cite. They are simply hungry for power and thus appropriate religion and use it to manipulate others into believing and ultimately behaving in ways that grant them that power.

But it’s not clear that this argument works, especially in the real world.

First, it seems unlikely that those who do evil in the name of religion don’t really believe the religious doctrines they espouse. The puritans in Salem probably wouldn’t have hung women as witches … unless they actually believed in witches. Most suicide bombers probably wouldn’t volunteer for suicide … unless they actually thought it guaranteed them an afterlife with 72 virgins. Evangelical Christians wouldn’t undermine science education by demanding equal time for young earth creationism … unless they actually believed the Earth was only 6000 years old. It’s not just a grab for power.

Second, even if religious leaders aren’t true believers (and are merely manipulating people to gain power), that wouldn’t mean religion isn’t dangerous. After all, the populace couldn’t be so easily manipulated if it weren’t for its religious beliefs. Puritanism could never take hold in a population made up of atheists. The question is whether society would be better off without religion; and if a lack of religion would make it less susceptible to such manipulation, the answer would seem to be yes.

To counter this, one might point to historical examples where people were manipulated to commit atrocities without the use of religion—like in Stalin’s Russia, Pol Pot’s Cambodia, or the Kim family’s North Korea. But there are two things to say in response.

First, the argument isn’t that a lack of religion would make it impossible to manipulate people—just that it would make it much harder. To think that the inability to completely eliminate something is a reason to do nothing about it commits what I call the “All or nothing” fallacy, a variety of false dichotomy. Yes, some leaders might still find ways to manipulate people, but if religion makes society more susceptible to manipulation, it’s dangerous. (This same fallacy is invoked by gun rights advocates who say that gun regulations are useless because they can’t stop all violent crime.)

Second, it’s not clear at all that Stalin, Pol Pot, and the Kim family did not use religion to manipulate people. Yes, their communist ideologies were based in a Marxist materialistic naturalism. But to solidify their power, these tyrants essentially invented their own religion that made them and their government the objects of worship.

Take North Korea where the Kim family created a religion, known as Juche, that literally worships them as gods. Their people actually believe them to be perfect and flawless … even capable of incredible feats like walking at 3 weeks old, talking at 8 weeks, driving at age 3, winning yacht races at age 9, writing 1500 books in 3 years, writing the 6 best operas in two … and (I kid you not) never going to the bathroom. Kim Jung-il even supposedly shot a 38 under par the first time he played a round of golf, which included 11 holes in one.

The New Atheists criticize all forms of blind devotion and willful ignorance. It’s not just supernatural beliefs that are dangerous, but the thought processes that generate and protect them. Even if they don’t consider Stalin and Pol Pot’s cult-of-personalities to be “religions” per se, the New Atheists do (at least) consider the “religious thinking” that makes such cults possible just as objectionable.

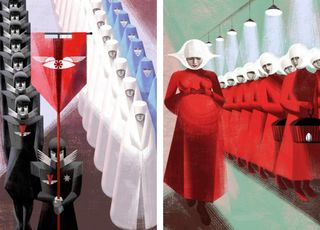

Illustrations from the Folio Society edition of The

Handmaid's Tale, by Anna and Elena Balbusso, that show how the

different "groups" dress.

Source: TheHandmaid'sTale/Anna and Elena Balbusso

And that brings us back around to feminism … because what (arguably) is most dangerous about both religion and secular personality cults is their authoritarianism—their unquestioned devotion to authority. And such devotion not only hinders personal freedom—but authority usually asserts itself by demonizing outsiders—racial minorities, other religions or nationalities … and genders. And the most effective way to do this is by entitativizing* them—treating the entire group as an entity, as if every member of the group is exactly the same.

Consider how every handmaid wears the same red dress and white bonnet. The commander’s barren wives all wear the same blue dress, the aunts the same brown suit—the marthas, the econowives—each member of each group wear the same thing. The message is clear: they are all the same.

The fallacy involved is called “hasty generalization.” You cannot generalize about an entire group based on a small sample. But feminists maintain that this is a primary way the patriarchy exercises its power against women.

If Bob can’t solve a math problem, we’re likely to conclude that Bobby is bad at math. But if Wendy can’t—it’s because all women are bad at math. We’ll do the same for driving, decision making … whatever is necessary to restrict their power. The Handmaid’s Tale fights against this by telling us what it is like to be a single member of such a group.

What makes The Handmaid’s Tale especially disturbing, however, is that it shows how authoritarianism can take hold even in the absence of an authority figure. The puritanism movement seems to have arisen organically; its leader is never mentioned. Indeed, this seems to be how many of the patriarchal assumptions in society have taken hold in the real world. No one person declared that women can’t vote, or should be restricted to household duties—societal assumptions about the abilities and role of all women simply became entrenched.

And it’s not just about women. As third-wavers often say, “patriarchy hurts men, too”—by, for example, instilling unrealistic, toxic, expectations regarding masculinity. Real men don’t cry; they must be dominant and self-reliant.

And it’s not just the patriarchy. Feminists can be guilty of this too—like how Offerd’s mother thinks that all men are only good for their sperm, or (in the real world) how “trans-exclusionary radical feminism” rejects all transgender women because they think they are simply men appropriating female-ness and disempowering women.

But what I think is most challenging about The Handmaid’s Tale is how it forces us to wrestle with our own complicity—complicity with the beliefs, assumptions, and power structures that make the kinds of exploitation we see in the book possible. Whether it be unjustified assumptions about gender or religions and religious beliefs that damage society—to the extent that one participates in such things, thus keeping them alive, it seems that one is morally culpable—at least to some degree.

In Virginia, a Murder by Mob law holds that, if you are participating in a riot, and another rioter murders someone—you too can be criminally charged. The law relies on a concept called “guilt by association.” And such guilt can be especially pronounced if—for example—someone who belongs to the same religion as you, does wrong in the name of a religious belief that you yourself hold. It would seem to follow that, if (as the New Atheists argue), religion does more harm than good—perhaps one should choose to no longer prop it up by being a member. And the same holds true for any sexist assumption you endorse explicitly in speech or implicitly in your actions. Even if you do no harm directly yourself, you are still guilty by association.**

In conclusion: Although Attwood did not intend for The Handmaid’s Tale to be feminist or anti-religious, I think we can see why it’s perceived that way. Attwood of course is free to interpret her own work as she sees fit, but if we reject intentionalism, and maintain that an author’s intention cannot solely define the meaning of his or her work, I believe that we can rightly maintain that seeing The Handmaid’s Tale as a feminist anti-religious tale, is (at the least) a legitimate interpretation.

Copyright 2018, David Kyle Johnson

*Thanks for the new word Jessica!

**Logic Note: I am not guilty of the "guilty by association" fallacy here--a version of the ad hominum fallacy that tries to dismiss the conclusion of a argument (or the evidence for a position) by pointing out that a disliked person or group agrees with it (e.g., "Global warming is a hoax because the unabomber believed it."). I am, instead, pointing out that voluntary members of a group morally share guilt with the crimes of the group. For more, see my paper on the topic.

References

Atwood, Margaret. “The Handmaid’s Tale.” Anchor. 1998.Tallman, Ruth. "Was it all a dream? Why Nolan's Answer doesn't matter."

Attwood,

Margaret. “Am I a bad feminist?” Globe and Mail (Opinion). Jan 13,

2018.

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/am-i-a-bad-feminist/article37591823

Baggini,

Julian. “Dan Dennett and the New Atheism.” The Philosophers’ Magazine.

May 08, 2017.

https://www.philosophersmag.com/interviews/31-dan-dennett-and-the-new-atheism

Comments

Post a Comment