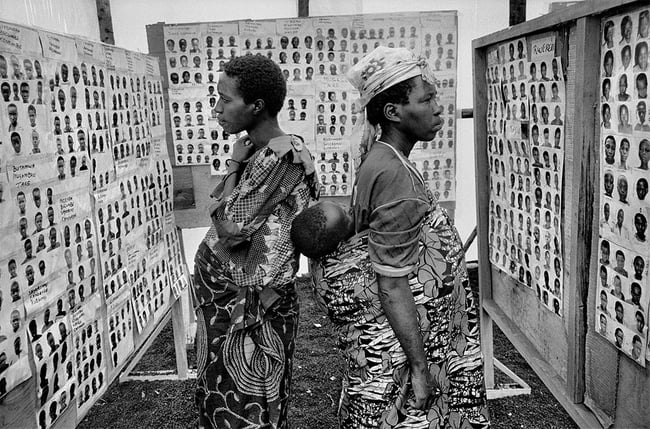

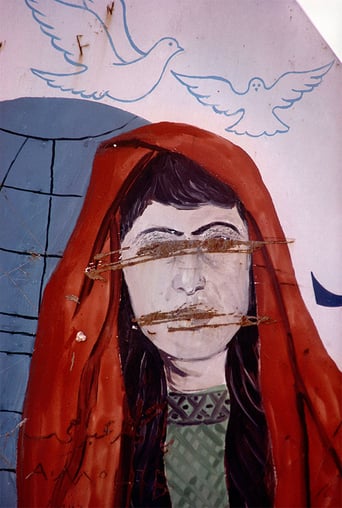

Empowering women to tell their stories

We have established a lot of material help in the camps. We know how to build tents, latrines, bring in doctors. The only thing that is missing is children’s education.

Letting children shape their story

Source: The UN refugee agency; Women’s Refugee Commission; Amnesty International; World Bank; World Health Organization and UN children’s fund

Low income

7.5m

11.1m

Low & middle income

16.9m

14.6m

Lower middle income

8.1m

2m

Middle income

9.3m

3.5m

Upper middle income

1.2m

1.4m

High income

12k

53k

1990

2015

The economics of being refugee

Source: World Bank

Source: The UN refugee agency

Mapping the world’s refugees

Syria – 5.5mAfghanistan – 2.5mSouth Sudan – 1.4mSomalia – 1mSudan – 650k

Top refugee countries

Top hosting countries

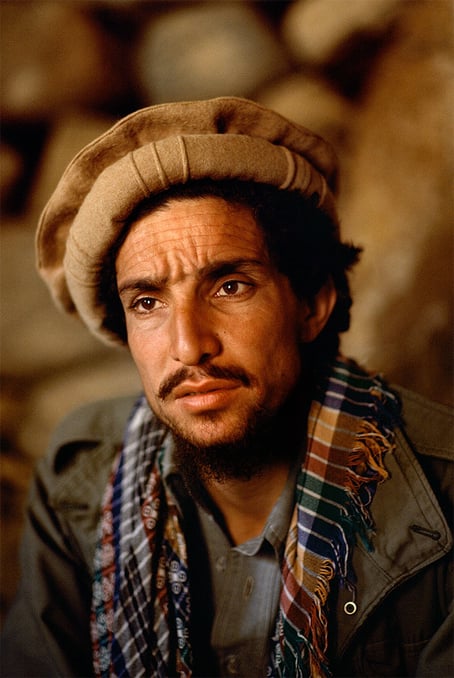

or magazines like National Geographic, Time and Life, photographer and

explorer Reza has traveled to more than a hundred countries, photographing conflicts, revolutions, and both manmade and natural disasters. The resulting photos of his half-century in the field are intended to capture the beauty of humanity that prevails despite the situation.

At age 10, Reza remembers starting to

comprehend the poverty he saw on the

streets of his native town of Tabriz, Iran.

He thought maybe others were too busy

to notice the people without shoes and

the humans who were sleeping on the

streets. He decided he’d take photographs

so other people would pay attention, too.

By 16, he published his first newspaper.

Two days after it came out, he was arrested

by the secret police and beaten because

in 1960s Iran it was forbidden to talk of

these things.

By 19, he had another idea. He’d enlarge

the images he took and post them on the

walls of his university in Tehran. He spent

age 22 through 25 in prison for his efforts.

For the first five months, he was tortured.

Then revolution came to Iran and he took photos of protesters. He was the first photographer on the scene when the news broke that American embassy staff had been taken hostage. He went on to cover the war in Kurdistan, then the Iran-Iraq conflict. But always he kept trying to find the beauty. “I believe the best thing we can do is create empathy,” he says. “You cannot create empathy by always showing burned kids and destroyed houses. People close their eyes; they don’t want to see it. Humans are humans, we only defend someone that we like or we love.”

In 1981, informed that the government was going to have him killed, he fled Iran and became an exile. Over the next decades, his lens focused on the siege of Beirut, followed by war in Afghanistan, followed by apartheid-era South Africa and Marcos’s Philippines. He later embedded himself with anti-Taliban forces and continues to document the plight of Afghans and Kurds. To date, he’s had more than a hundred of his stories published.

In 2001, he started his first NGO – in Afghanistan and called AinaWorld – based on empowering local women to become journalists, photographers and filmmakers. Other NGOs he has more recently founded – like Reza Visual Academy – focus on training refugee children and the children of the world’s poorest neighborhoods to tell their stories. He then creates local exhibitions of the work. For Reza, these exhibitions say, “We the people of this neighborhood, this is who we are.” He adds, “It is a tool to create understanding, to combat enmity .”

explorer Reza has traveled to more than a hundred countries, photographing conflicts, revolutions, and both manmade and natural disasters. The resulting photos of his half-century in the field are intended to capture the beauty of humanity that prevails despite the situation.

At age 10, Reza remembers starting to

comprehend the poverty he saw on the

streets of his native town of Tabriz, Iran.

He thought maybe others were too busy

to notice the people without shoes and

the humans who were sleeping on the

streets. He decided he’d take photographs

so other people would pay attention, too.

By 16, he published his first newspaper.

Two days after it came out, he was arrested

by the secret police and beaten because

in 1960s Iran it was forbidden to talk of

these things.

By 19, he had another idea. He’d enlarge

the images he took and post them on the

walls of his university in Tehran. He spent

age 22 through 25 in prison for his efforts.

For the first five months, he was tortured.

Then revolution came to Iran and he took photos of protesters. He was the first photographer on the scene when the news broke that American embassy staff had been taken hostage. He went on to cover the war in Kurdistan, then the Iran-Iraq conflict. But always he kept trying to find the beauty. “I believe the best thing we can do is create empathy,” he says. “You cannot create empathy by always showing burned kids and destroyed houses. People close their eyes; they don’t want to see it. Humans are humans, we only defend someone that we like or we love.”

In 1981, informed that the government was going to have him killed, he fled Iran and became an exile. Over the next decades, his lens focused on the siege of Beirut, followed by war in Afghanistan, followed by apartheid-era South Africa and Marcos’s Philippines. He later embedded himself with anti-Taliban forces and continues to document the plight of Afghans and Kurds. To date, he’s had more than a hundred of his stories published.

In 2001, he started his first NGO – in Afghanistan and called AinaWorld – based on empowering local women to become journalists, photographers and filmmakers. Other NGOs he has more recently founded – like Reza Visual Academy – focus on training refugee children and the children of the world’s poorest neighborhoods to tell their stories. He then creates local exhibitions of the work. For Reza, these exhibitions say, “We the people of this neighborhood, this is who we are.” He adds, “It is a tool to create understanding, to combat enmity .”

F

Refugees are the vulnerable. They have lost everything in a second, in a day. Refugees are like a flower that you are cutting and putting in the wind.

National Geographic photographer Reza helps refugees tell their stories

Paid for by

P e r s o n a l I n v e s t m e n t s

Comments

Post a Comment